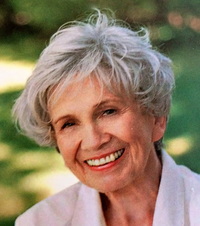

Alice Monro

Alice Monro I’m going to say flat out that Munro is the greatest living writer, and that Dear Life, was my favorite book of 2013. The fact that I’d read most of the stories before made it even better. This morning, I re-read one that I had not yet read twice, a story called Dolly about a woman in her seventies and her older mate, and a sudden flare of jealousy that brings them back into the car where the story started. A car where they had been planning their premature joint suicide, right down to the note or no-note question.

The full circle-ness of Dolly made we wonder how Munro writes. Certainly her work gives the impression that nothing was planned, that the particulars just got more particular as she went along, that any coincidence of an ending being perfectly crafted is purely accidental. Perhaps she writes and rewrites and rewrites as I do, as I believe any serious storyteller must do, until the clear meaning emerges from the block of marble. Or perhaps she sees it all in her head in advance.

Here I think it necessary to pull a Franzen and bring in an off-topic memory of my brother-in-law, Jerry, clever and talented in his youth, witty still in his fifties, dead at fifty-six, who held up that idea of a perfect first draft, no editing necessary, Ernest Hemmingway channeled straight onto the page, thank you very much. This concept certainly kept him from trying any serious adult writing, was a good excuse to have another beer or five and drift off into belligerence and blustering and bragging about the some ancient flicker of talent he’d once known he possessed.

Back to Munro: what do I so love about her? Certainly the best fiction sets us dreaming about our own life, inspires us to take up our creative work, makes us want to be better. Munro gives me the courage to dust off a fragment of a story and see if it goes anywhere, to simply follow it as far as it can go today, to take pleasure in the act of writing. Can I say that like Jack Nicholson in As Good as it Gets, she makes me want to be a better woman?

Maybe a worse one, maybe a more real one. Because Munroe is a realist, so real as to bring us off our literary cloud and back to the earth in all its awesome sweetness and reality.

It’s all about the people. It’s all about life.

On one level, Munro’s work is full of clever little insights, pleasing little appetizers, and buried truths. Her dialogue always rings true. Her prose is easy and precise, never jarring or overly flashy. My internal editor is not even set on vibrate. Because she is the master, and I am not worthy of being her apprentice (in the most unlikely event that she should decide to take me on) I let myself relax into a pleasant state of awe-tinged enjoyment. Savoring, noticing, moving on to the next bite.

Deeper still is a sense of eavesdropping on people who are just a little worse than ourselves. Or perhaps we’d be much the same if we dared. The plainness of her characters gives us the false sense of superiority. Then they speak for us in their modest way and that sneaks up on us. Let’s us see the human beast we are.

At the next level is surprise. Yes, this could happen, this could be. This is how it might end, and wow, why didn’t I think of that?

Each time I read Munro, I plunge into the greatness of her art and the mystery of what makes it so. My pure pleasure at her offering deepens on each subsequent read. Dear Life might be her best collection, or it might not. There is certainly never any faltering. She is the master. She just is. What have you to show me today, I ask? What did I miss out on yesterday? I would wallow in her work.

I know my own ambitions benefit from studying Munro and even Franzen’s own fiction and his review of Munro. Because they set the bar so high, I have permission to aspire to excellence, to make my work as good as possible, at whatever risk of slowness, perceived lack of ambition, late bloomer-ness, whatever deficit of self-promotion. Because that’s what I care most about. That the work be good.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed